Heronian triangle

In geometry, a Heronian triangle is a triangle whose sidelengths and area are all rational numbers. It is named after Hero of Alexandria. Any such rational triangle can be scaled up to a corresponding triangle with integer sides and area, and often the term Heronian triangle is used to refer to the latter.

Contents |

Properties

Any triangle whose sidelengths are a Pythagorean triple is Heronian, as the sidelengths of such a triangle are integers, and its area (being a right-angled triangle) is just half of the product of the two sides at the right angle.

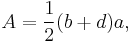

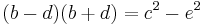

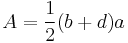

An example of a Heronian triangle which is not right-angled is the one with sidelengths 5, 5, and 6, whose area is 12. This triangle is obtained by joining two copies of the right-angled triangle with sides 3, 4, and 5 by the side of length 4. This approach works in general, as illustrated in the picture to the right. One takes a Pythagorean triple (a, b, c), with c being largest, then another one (a, d, e), with e being largest, constructs the triangles with these sidelengths, and joins them together by the side of length a, to obtain a triangle with integer sidelengths c, e, and b + d, with rational area

(one half times the base times the height).

(one half times the base times the height).

An interesting question to ask is whether all Heronian triangles can be obtained by joining together two right-angled triangles described in this procedure. The answer is no. If one takes the Heronian triangle with sidelengths 0.5, 0.5, and 0.6, which is just the triangle described above shrunk 10 times, it clearly cannot be decomposed into two triangles with integer sidelengths. Nor for example can a 5, 29, 30 triangle with area 72, since none of its altitudes are integers. However, if one allows for Pythagorean triples with rational entries, not necessarily integers, then the answer is affirmative,[1] because every altitude of a Heronian triangle is rational (since it equals twice the rational area divided by the rational base). Note that a triple with rational entries is just a scaled version of a triple with integer entries.

Theorem

Given a Heronian triangle, one can split it into two right-angled triangles, whose sidelengths form Pythagorean triples with rational entries.

Proof of the theorem

Consider again the illustration to the right, where this time it is known that c, e, b + d, and the triangle area A are rational. We can assume that the notation was chosen so that the sidelength b + d is the largest, as then the perpendicular onto this side from the opposite vertex falls inside this segment. To show that the triples (a, b, c) and (a, d, e) are Pythagorean, one must prove that a, b, and d are rational.

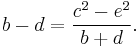

Since the triangle area is

one can solve for a to find

which is rational, as both  and

and  are rational. Left is to show that b and d are rational.

are rational. Left is to show that b and d are rational.

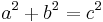

From the Pythagorean theorem applied to the two right-angled triangles, one has

and

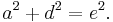

One can subtract these two, to find

or

or

The right-hand side is rational, because by assumption, c, e, and b + d are rational. Then, b − d is rational. This, together with b + d being rational implies by adding these up that b is rational, and then d must be rational too. Q.E.D.

Exact formula for Heronian triangles

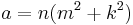

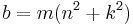

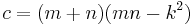

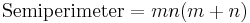

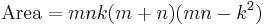

All Heronian triangles can be generated [2] as multiples of:

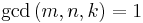

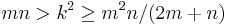

for integers m, n and k subject to the contraints:

.

.

See also Heronian triangles with one angle equal to twice another.

Examples

The list of fundamental integer Heronian triangles, sorted by area and, if this is the same, by perimeter, starts as in the following table. Fundamental means that the greatest common divisor of the three side lengths equals 1.

| Area | Perimeter | length b+d | length e | length c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 12 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| 12 | 16 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| 12 | 18 | 8 | 5 | 5 |

| 24 | 32 | 15 | 13 | 4 |

| 30 | 30 | 13 | 12 | 5 |

| 36 | 36 | 17 | 10 | 9 |

| 36 | 54 | 26 | 25 | 3 |

| 42 | 42 | 20 | 15 | 7 |

| 60 | 36 | 13 | 13 | 10 |

| 60 | 40 | 17 | 15 | 8 |

| 60 | 50 | 24 | 13 | 13 |

| 60 | 60 | 29 | 25 | 6 |

| 66 | 44 | 20 | 13 | 11 |

| 72 | 64 | 30 | 29 | 5 |

| 84 | 42 | 15 | 14 | 13 |

| 84 | 48 | 21 | 17 | 10 |

| 84 | 56 | 25 | 24 | 7 |

| 84 | 72 | 35 | 29 | 8 |

| 90 | 54 | 25 | 17 | 12 |

| 90 | 108 | 53 | 51 | 4 |

| 114 | 76 | 37 | 20 | 19 |

| 120 | 50 | 17 | 17 | 16 |

| 120 | 64 | 30 | 17 | 17 |

| 120 | 80 | 39 | 25 | 16 |

| 126 | 54 | 21 | 20 | 13 |

| 126 | 84 | 41 | 28 | 15 |

| 126 | 108 | 52 | 51 | 5 |

| 132 | 66 | 30 | 25 | 11 |

| 156 | 78 | 37 | 26 | 15 |

| 156 | 104 | 51 | 40 | 13 |

| 168 | 64 | 25 | 25 | 14 |

| 168 | 84 | 39 | 35 | 10 |

| 168 | 98 | 48 | 25 | 25 |

| 180 | 80 | 37 | 30 | 13 |

| 180 | 90 | 41 | 40 | 9 |

| 198 | 132 | 65 | 55 | 12 |

| 204 | 68 | 26 | 25 | 17 |

| 210 | 70 | 29 | 21 | 20 |

| 210 | 70 | 28 | 25 | 17 |

| 210 | 84 | 39 | 28 | 17 |

| 210 | 84 | 37 | 35 | 12 |

| 210 | 140 | 68 | 65 | 7 |

| 210 | 300 | 149 | 148 | 3 |

| 216 | 162 | 80 | 73 | 9 |

| 234 | 108 | 52 | 41 | 15 |

| 240 | 90 | 40 | 37 | 13 |

| 252 | 84 | 35 | 34 | 15 |

| 252 | 98 | 45 | 40 | 13 |

| 252 | 144 | 70 | 65 | 9 |

| 264 | 96 | 44 | 37 | 15 |

| 264 | 132 | 65 | 34 | 33 |

| 270 | 108 | 52 | 29 | 27 |

| 288 | 162 | 80 | 65 | 17 |

| 300 | 150 | 74 | 51 | 25 |

| 300 | 250 | 123 | 122 | 5 |

| 306 | 108 | 51 | 37 | 20 |

| 330 | 100 | 44 | 39 | 17 |

| 330 | 110 | 52 | 33 | 25 |

| 330 | 132 | 61 | 60 | 11 |

| 330 | 220 | 109 | 100 | 11 |

| 336 | 98 | 41 | 40 | 17 |

| 336 | 112 | 53 | 35 | 24 |

| 336 | 128 | 61 | 52 | 15 |

| 336 | 392 | 195 | 193 | 4 |

| 360 | 90 | 36 | 29 | 25 |

| 360 | 100 | 41 | 41 | 18 |

| 360 | 162 | 80 | 41 | 41 |

| 390 | 156 | 75 | 68 | 13 |

| 396 | 176 | 87 | 55 | 34 |

| 396 | 198 | 97 | 90 | 11 |

| 396 | 242 | 120 | 109 | 13 |

Almost-equilateral Heronian triangles

A Heronian triangle is a triangle with rational sides, area and inradius. Since the area of an equilateral triangle with rational sides is an irrational number, no equilateral triangle is Heronian. However, there is a unique sequence of Heronian triangles that are "almost equilateral" because the three sides, expressed as integers, are of the form n − 1, n, n + 1. The first few examples of these almost-equilateral triangles are set forth in the following table.

| Side length | Area | Inradius | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n − 1 | n | n + 1 | ||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 84 | 4 |

| 51 | 52 | 53 | 1170 | 15 |

| 193 | 194 | 195 | 16296 | 56 |

| 723 | 724 | 725 | 226974 | 209 |

| 2701 | 2702 | 2703 | 3161340 | 780 |

| 10083 | 10084 | 10085 | 44031786 | 2911 |

| 37633 | 37634 | 37635 | 613283664 | 10864 |

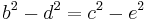

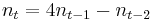

Subsequent values of n can be found by multiplying the last known value by 4, then subtracting the next to the last one (52 = 4 × 14 − 4, 194 = 4 × 52 − 14, etc), as expressed in

where t denotes any row in the table.

This sequence (sequence A003500 in OEIS) can also be generated from the solutions to the Pell's equation x² − 3y² = 1, which can in turn be derived from the regular continued fraction expansion for √3.[3]

See also

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Heronian triangle" from MathWorld.

- Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences Heronian

- Wm. Fitch Cheney, Jr., Heronian Triangles Am. Math. Montly 36 (1) (1929) 22-28.

- S. sh. Kozhegel'dinov On fundamental Heronian triangles Math. Notes 55 (2) (1994) 151-156.

References

- ^ Sierpiński, Wacław, Pythagorean Triangles, Dover Publ., 2003 (orig. 1962).

- ^ Carmichael, R. D., 1914, "Diophantine Analysis", pp.11-13; in R. D. Carmichael, 1959, The Theory of Numbers and Diophantine Analysis, Dover.

- ^ William H. Richardson (2007), Super-Heronian Triangles.